Students in the WU-CRRJ Action Research Lab use archival research techniques to help redress the legacy of racial violence in Missouri and beyond.

When SaMiya Carroll, a junior majoring in sociology, first applied to work in the Civil Rights & Restorative Justice (CRRJ) Action Research Lab at WashU, she wasn’t sure exactly what she’d be doing, but she was excited to dive in.

David Cunningham, chair and professor of sociology, and Geoff Ward, professor of African and African American studies and director of the WashU & Slavery Project, launched the lab last year in partnership with the award-winning CRRJ Clinic at the Northeastern University School of Law. That program aims to give students an opportunity to put their research skills to productive use while also redressing the national legacy of racial violence. Since then, the WashU Action Research Lab has expanded its scope to include Cunningham and Ward's Virality of Racial Terror project, allowing the lab to serve as a freestanding space connecting students to research on a variety of projects related to racial justice.

Last year, WashU Action Research Lab students investigated unsolved homicides in Missouri between 1930 and 1954 to determine if the killings were racially motivated. Their findings were then passed to law students at Northeastern in an attempt to rectify racial violence using legal means. “Throughout history, there’s been a lot of violence done to the Black body,” Carroll said. “Our work is about uncovering that.”

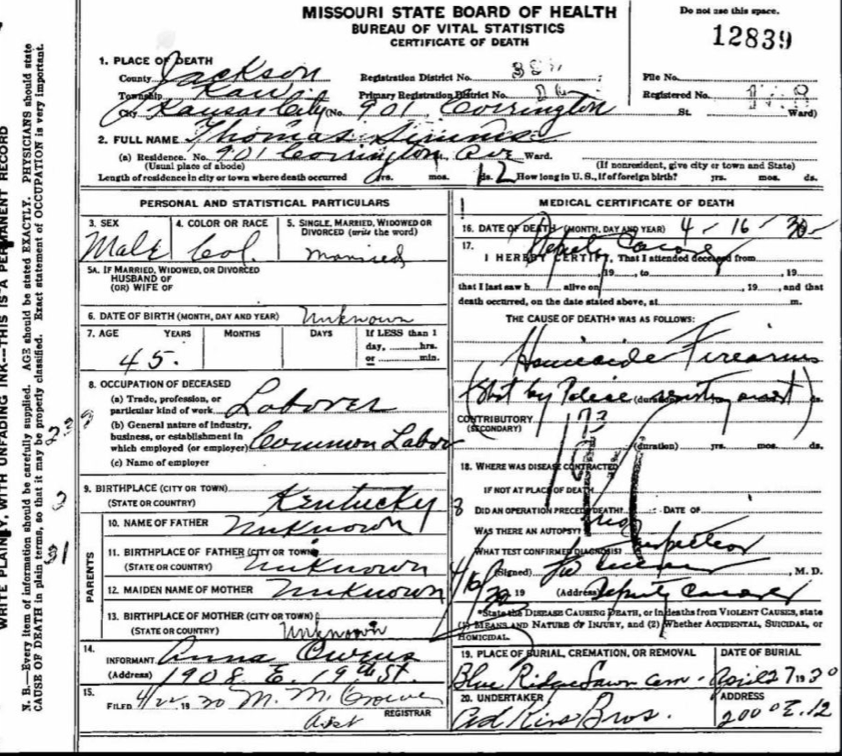

Carroll researched the case of Tom Sims, a Black man killed in 1930 during a shootout with Kansas City police. As she dug through newspaper clippings, marriage records, and death records, she uncovered many puzzle pieces connecting his life. In the end, Carroll and the team were unable to conclusively determine if Sims' death was motivated by his race. “I had many hypotheses about what happened but, eventually, we hit a wall.” Still, she was amazed at how much she was able to discover about Sims through archival research.

Last semester, Carroll switched her focus to community-level violence, such as racial massacres and lynchings. She was surprised to find the historical events she was researching suddenly seemed far more personal. Carroll’s grandfather was born in southern Mississippi in the early 1940s, a time of widespread racial terror that included the lynching of Emmett Till the following decade and widespread violence against civil rights activists in the 1960s.

Speaking with her grandparents, Carroll realized the racialized violence she was studying in the lab had affected her family just two generations prior. Her grandfather said his primary school — a building Black families built when their children were banned from attending the local white school — was burned down by white citizens in an act of racial violence. “I asked my grandfather if the stories I was reading about were really that common,” she said. “I came to realize that, actually, it’s really close to my own family.”

Carroll said working in the WashU Action Research Lab has improved her research skills, particularly when it comes to navigating newspaper archives. The work has helped students see the effects of structural poverty and racism on individual lives — insights with the power to rectify legacies of racial injustice.

“Newspaper research can seem mundane,” Carroll said. “But if you keep going, you begin to see how one piece connects to another. We can uncover what happened, pull out specific pieces, and build a story.”